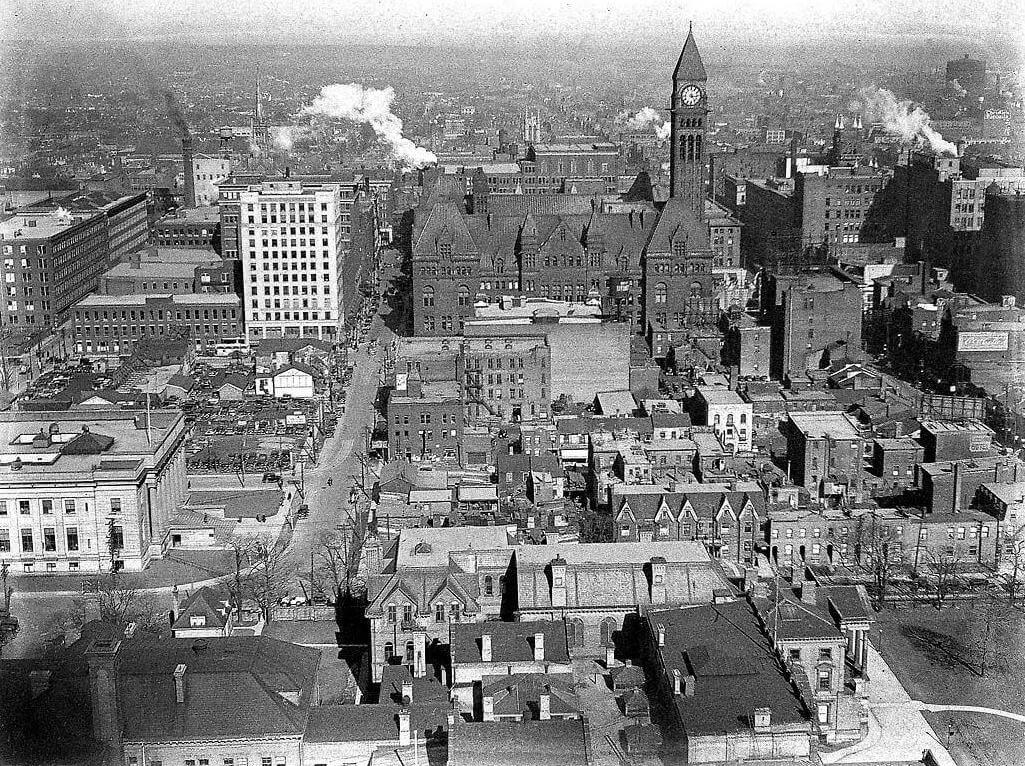

In November, 1912, a small group of prominent Toronto businessmen, including John Macdonald, a director at the Bank of Toronto, John Firstbrook, a director at The Metropolitan Bank, and John I. Sutcliffe, a chartered accountant, met to discuss ways to improve city government. By meeting’s end, Mr. Sutcliffe was selected to undertake a special mission: travel to New York and investigate the work of a civic organization known as the New York Bureau of Municipal Research.

New York Roots

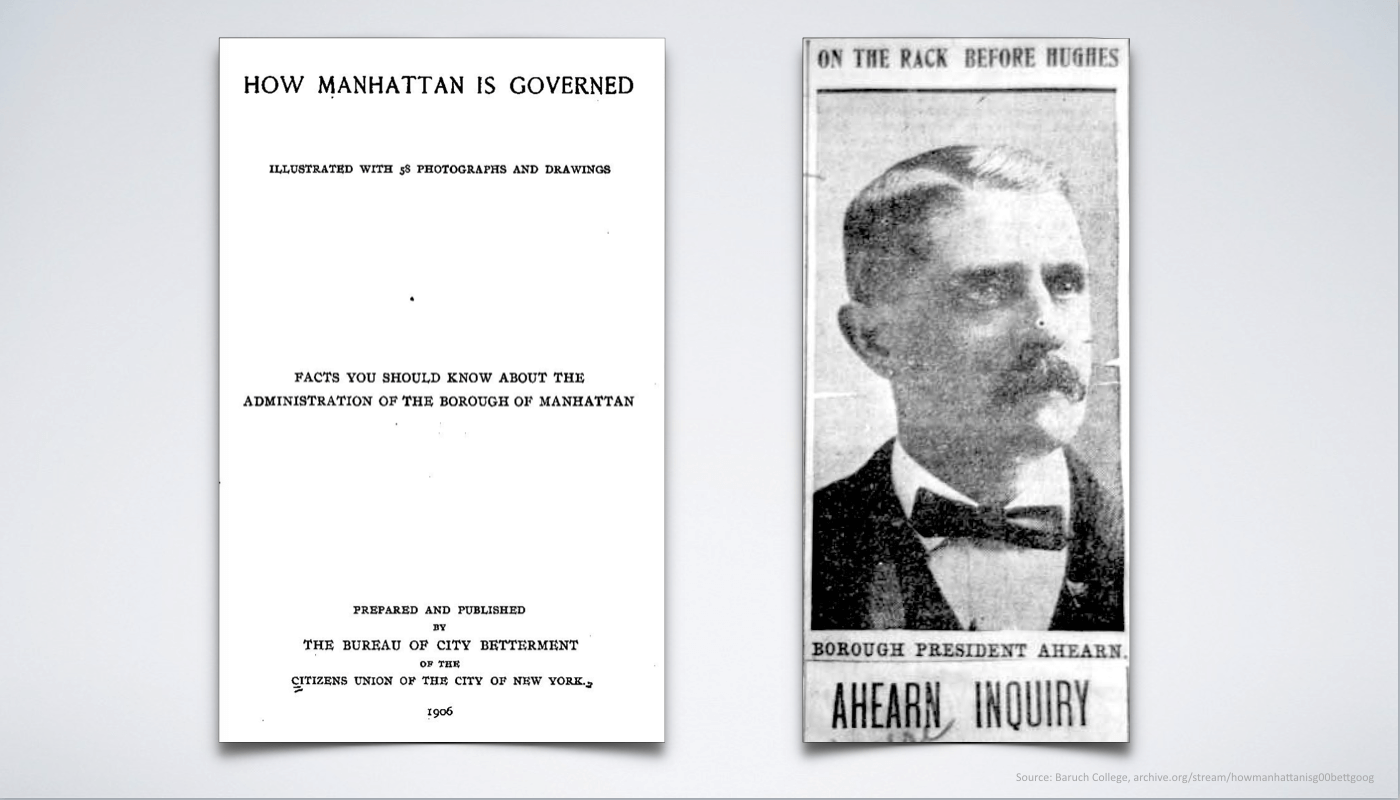

The New York Bureau was established in 1907 as part of the emerging municipal reform movement during the so-called Progressive Era. Its founders — William Allen, Henry Bruere, and Frederick Cleveland — conceived of the Bureau as means to expose incompetence and mismanagement within city government, at a time when New York, and many other American cities, were dominated by machine politics and neighbourhood bosses. “The Bureau men,” recounts Jane Dahlberg, “were essentially reformers with the idea that a citizen organization could help to improve its government by applying principles of good management to public affairs.”1 The group’s emphasis on “municipal research” conveyed its faith in objective truth, empirical measurement, and expert analysis — in essence, the pursuit of a science of government.

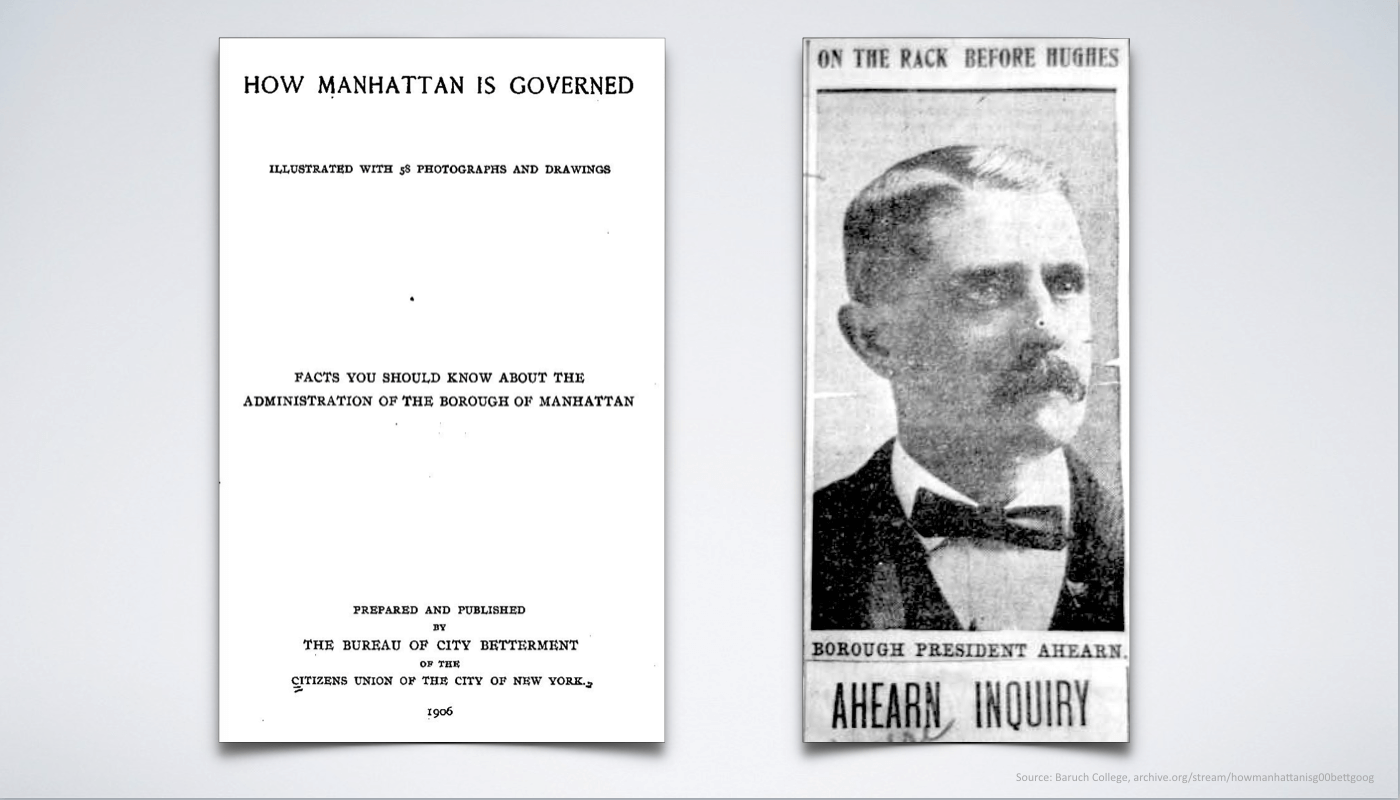

Backed by some of New York’s wealthiest philanthropists, including Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, the Bureau’s first study, How Manhattan is Governed, documented waste and negligence within the office of Manhattan Borough President John Ahearn, a member of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine. Bureau researchers carefully scrutinized municipal maintenance records to find that, in many instances, streets, sewers, and public baths that had been officially reported as repaired were still in poor condition. The Bureau’s findings led to a series of official inquiries and public hearings, and eventually, Ahearn’s removal from office — the first time an American elected official was dismissed due to incompetence, rather than dishonesty or corruption. The scandal earned the Bureau considerable notoriety, and similar bureaus were soon opened in over a dozen cities across the United States, including Philadelphia (1908), Cincinnati (1909), Chicago (1910), and Milwaukee (1913).2

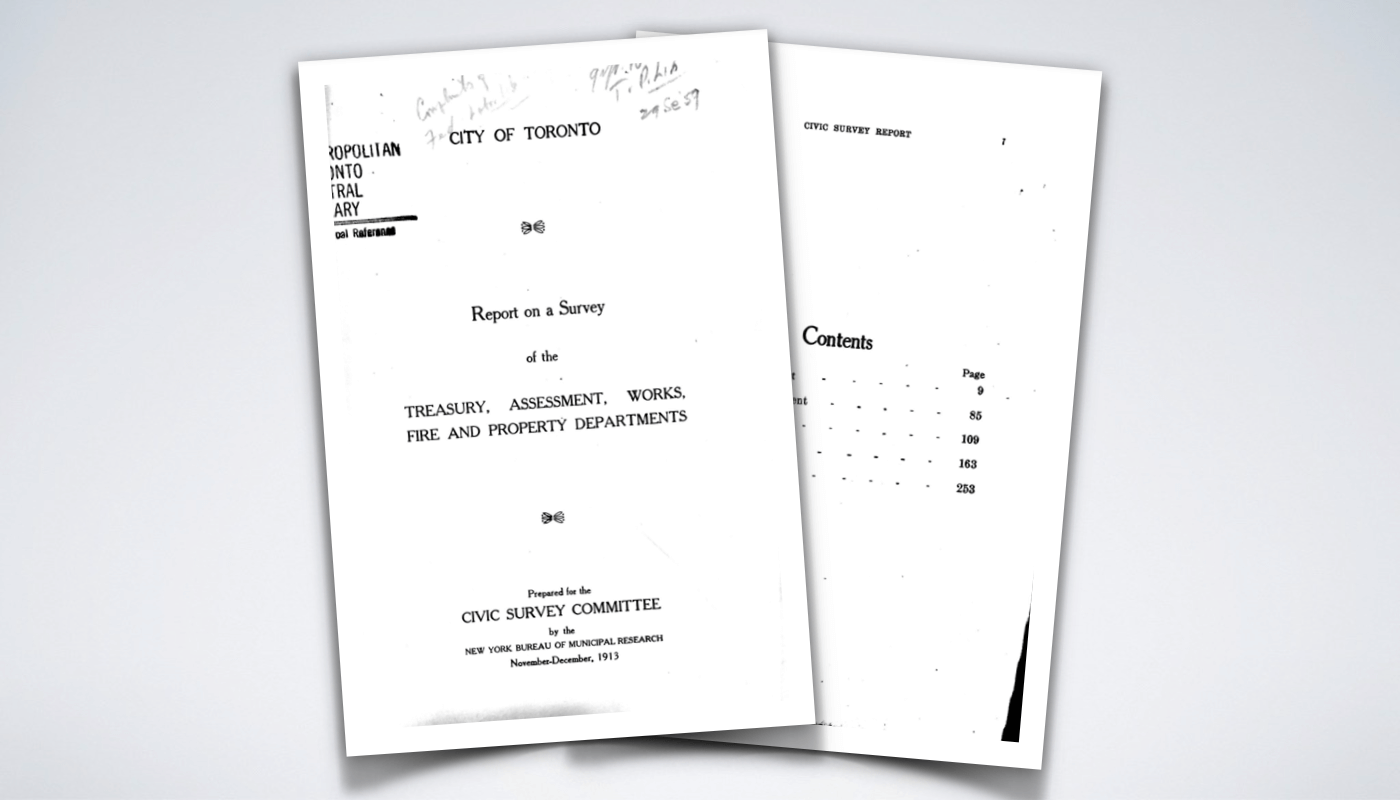

Toronto Civic Survey

Sutcliffe returned to Toronto thoroughly impressed. With the support of Alderman S. Morley Wickett, the group invited Henry Bruere to speak at the National Club. Bruere urged members to commission a comprehensive survey of Toronto’s municipal departments, services, and administrative methods. According to local reports, Bruere’s address drew “frequent and hearty applause from his hearers.”3

A “Committee of One Hundred Citizens” was soon struck to raise funds under the auspices of a Civic Survey Committee. Members pledged at least $50 toward the endeavour, raising a total of $6,000 (approx. $128,000 in current dollars). The Committee commissioned staff from the New York Bureau to carry out the study in late 1913. After two months of investigation, the researchers returned with their findings, spanning nearly 300 pages. The study concluded that Toronto’s “administrative defects are primarily those of methods and not of men.”4 By establishing a permanent bureau in Toronto to improve financial reporting practices, reorganize the municipal workforce, and employ principles of scientific management, the city could achieve cost savings of approximately five to ten percent.

Founding Principles

Once published in January 1914 (view PDF), the Toronto Daily Star hailed the report as “the most important ever submitted on the municipal affairs of this city,” and welcomed the establishment of a permanent local bureau to serve as a “centre of general municipal intelligence.”4 The Toronto Bureau of Municipal Research was born two weeks later.

Consistent with the guiding philosophy of its parent organization, the Toronto Bureau was premised on four founding principles:

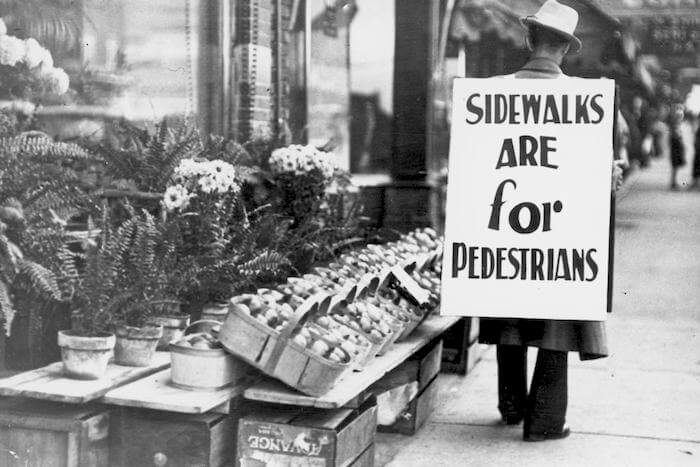

1. A commitment to scientific inquiry. Scientific methods were expected to produce factual knowledge that would identify the most efficient and economical means of providing public services.

2. Civic responsibility. Bureau members believed that public officials, whether elected or appointed, had a responsibility to respect the division between politics and administration. Administrative matters should be led by trained professionals and experts, not politicians; citizens, in turn, had a responsibility to be aware of and informed about how government works, and to keep governments accountable.6

3. Publicity. Reform requires political support and public pressure. By publicizing its findings, the Bureau hoped to mobilize citizens, and thus drive change.

4. Non-partisanship. The Bureau’s political approach was pragmatic, not personal. As founding chairman John Sutcliffe put it, “It is a cardinal principle [of all bureaus of municipal research] never to advocate or oppose the election or appointment of any man to any office.”7 Reports rarely, if ever, included accusations of personal wrongdoing or forms of “muckraking” found in the tabloids.

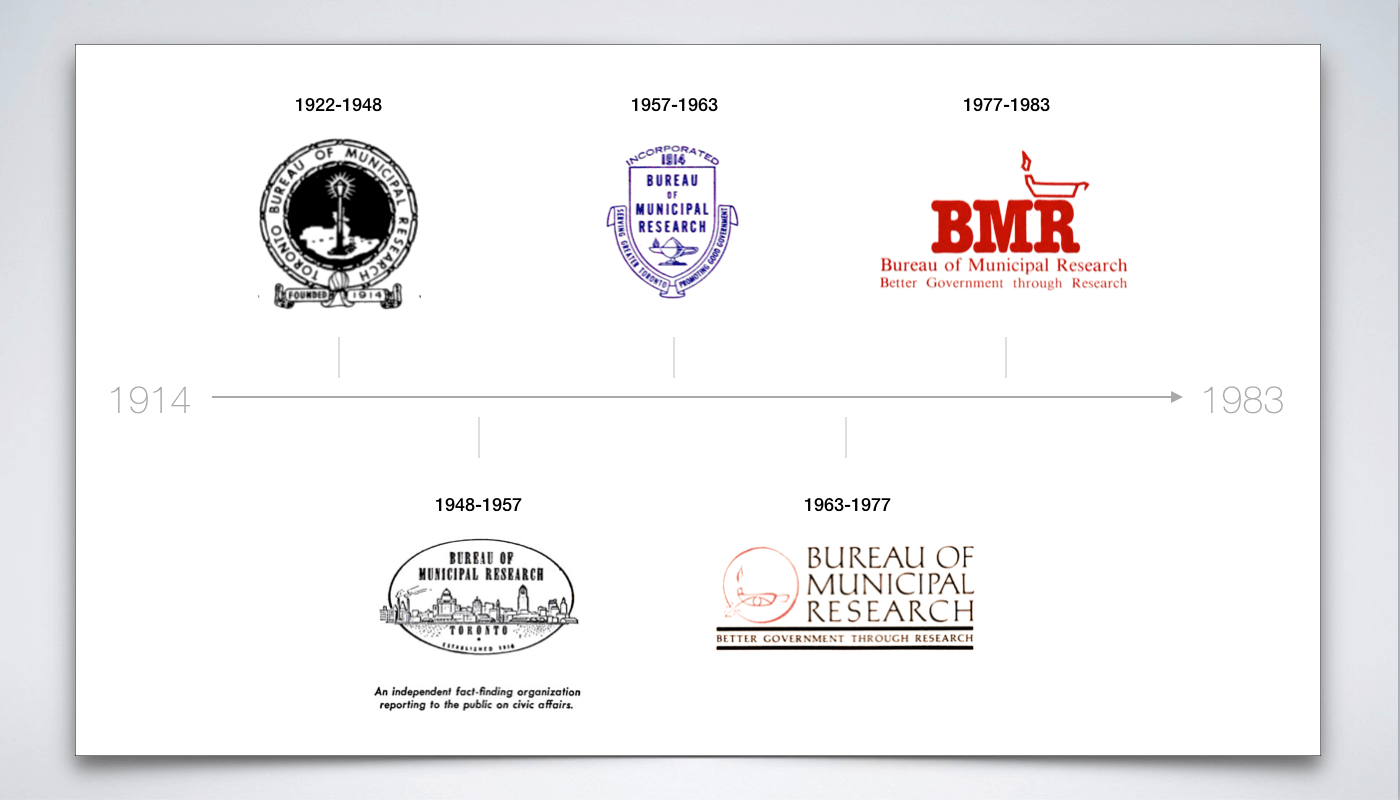

Organizational Evolution

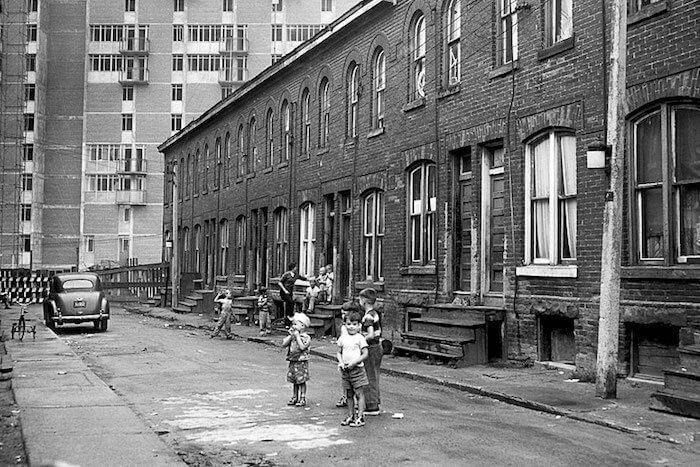

The Bureau was originally funded by prominent members of Toronto’s business establishment, including the Gooderham family of distillers. Its emphasis on professionalism and efficient management appealed to civic elites who valued political stability in a period of social and economic change, when high rates of immigration and unionization posed a potential risk to upper and middle class interests. The early Bureau thus had little trouble attracting patrons from prestigious private clubs, such as The Toronto Club and the National Club, to serve as trustees, executives, and elected “council” members.

As the Bureau evolved, it eventually sought donations from corporations and business groups, in addition to individual donations. For decades, the Bureau publicized its financial independence as proof of its impartiality.

1924: “The Toronto Bureau of Municipal Research derives its financial support from voluntary contributions of public-spirited citizens. As provided in its charter it receives no government or municipal grants. It has no axe to grind other than effective citizenship. It has no strings on it save its attachment to the interests of Toronto.”

1936: “The Bureau of Municipal Research is an independent, non-partisan agency, carried on in the interests of all taxpayers and citizens by voluntary contributions of some citizens. Naturally it receives, and can receive, no support from governmental or municipal sources. It ascertains facts as to municipal government, analyzes these facts, and presents the results to the general public, along with constructive suggestions based on the facts. It backs no candidates, recommends no one for civic appointment, and has no axe to grind other than that of those who use and directly or indirectly pay for the cost of municipal services.”

1960: “The Bureau of Municipal Research is... Enterprising — the only research organization concerned exclusively with improving local government operations and practices throughout Greater Toronto. Public spirited — a non-profit agency backed by business concerns, associations and individuals who want honest, efficient government. Independent — by its provincial charter, barred from accepting government subsidy and committed to a continuing and impartial survey of civic affairs.”

But as corporate and individual donations started to decline in the early 1960s, the Bureau was forced to expand its membership. Initially, it raised funds from academic institutions (mainly university libraries) and labour groups, such as the Ontario Federation of Labour. Later, it started to receive contributions from the City of Toronto, the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. By the early 1980s, the Bureau relied on financial support from at least 27 government bodies. The financial lifeline provided by government grants, however, proved to be short-lived.

In 1983, the Ontario government decided not to renew a $25,000 annual grant. The Bureau had little choice but to close shop. The Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto agreed to provide the Bureau a final grant of $35,000 to pay off its creditors and provide severance pay to staff. In exchange, the Bureau transferred over its complete research library to the Metro Toronto Public Library.

Notes

1. Jane S. Dahlberg, The New York Bureau of Municipal Research: Pioneer in Government Administration (New York: New York University Press, 1966), 231.

2. Bureaus were often established under slightly different names, such as the Bureau of Public Efficiency, in Chicago, or the Citizens’ Bureau of Municipal Efficiency, in Milwaukee.

3. “Civic Pride Is First Need for Efficiency,” The Globe, July 11, 1913.

4. New York Bureau of Municipal Research, City of Toronto Report on a Survey of the Treasury, Assessment, Works, Fire, and Property Departments (New York: New York Bureau of Municipal Research, 1913), 5.

5. “Survey Experts Plan to Remedy Defects Found,” Toronto Daily Star, January 8, 2014.

6. These two goals may appear contradictory. But not to members of the Bureau, who believed that scientific knowledge (if properly communicated) was fundamentally democratic. Knowledge, in short, enabled public scrutiny.

7. John I. Sutcliffe, “Municipal Research Work,” The Globe, December 25, 1914.

8. Bureau of Municipal Research, Open Letter to the Citizens and Taxpayers of Toronto, White Paper no. 78 (1924).

9. Bureau of Municipal Research, Open Letter, Bulletin no. 94 (1936).

10. Bureau of Municipal Research, The Study of the Economic Impact of Urban Expressway Upon Adjacent Areas (1960).